Q&A with Jay Rosen: How Trump nullifies reality

Media critic says lies should be called lies, but the word has “no magic powers.”

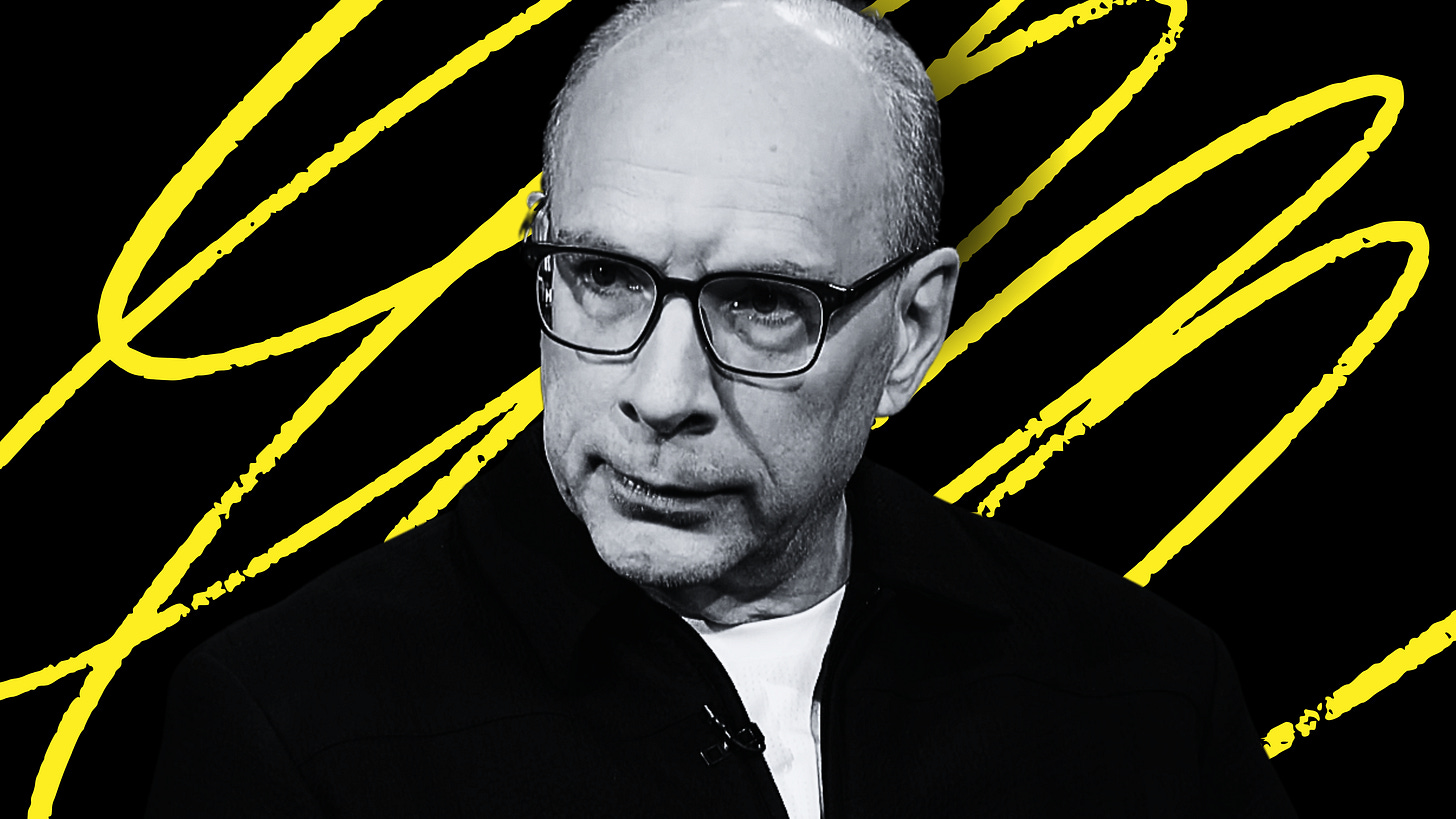

Jay Rosen, who recently retired from teaching after 39 years at New York University, is one of journalism’s most influential and incisive thinkers. His 1999 book “What Are Journalists For?” was a call to revitalize the news profession, and his current website PressThink continues in that vein as the industry is besieged by political pressure and disinformation.

Jay agreed to a Q&A with me about how journalists can respond in this time of crisis.

Jacob: You’ve coined a term called “verification in reverse” to describe performative lying by authority figures, such as House Speaker Mike Johnson saying public approval of Donald Trump is at 90%, which is ridiculous. Can you explain what you mean by that term?

Rosen: Verification is the heart of modern journalism — and its most important practice. What I mean by “verification” is pretty simple. It’s the impulse to ask, “Did that really happen?” and the practice of finding out.

Verification is behind the newsroom’s favorite joke. “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” Among the agreed-upon virtues that bind journalists together, verification is at or near the very top. Which is why I wrote a PressThink post called “Good Old Fashioned Shoe Leather Reporting.” The image is of knocking on many, many doors to ask those who might know, “Did that really happen?” So many doors that you wear a hole in your shoes.

It’s important to add: Verification is real. Which means it can fail. At times we ask, “Did that really happen?” and the only honorable answer is “We don’t know.” Still, verification has immense status in modern journalism.

If verification is nailing down truth claims with facts, data, documents, video, and testimony, verification in reverse means taking facts that have been nailed down and introducing doubt about them. With this doubt comes friction, controversy, commotion, emotion, backlash, accusation, disgust, momentum. And with the energy released by these reactions you can power your political movement. As Donald Trump did with his birtherism.

It’s not just a big, fat lie that you want people to swallow. It’s that plus. The plus is the way verification in reverse weakens the whole idea of asking, “Did that really happen?”

Jacob: So, in effect, verification in reverse devalues the whole idea of facts, right? I worry that propagandists, and some journalists by extension, act as if everything is merely an opinion — that nothing is a settled fact. And that way, a lie is not a lie — it’s just a not-yet-proven fact. Can a democracy survive in that atmosphere?

Rosen: No. It cannot. The shock to the system is too big. If everything is just a malleable opinion we can never get our bearings and know where we are in real time.

Here I need to emphasize that an authoritarian ruler can go well beyond lying to the press, or keeping journalists in the dark. Beyond intimidation or legal action, as well. There’s another route he can take. He can teach his movement — and his government — to reject reality on a sweeping scale, and discredit the whole idea that we can know what’s happening in our world. Instead of jailing journalists, nullify the real.

Here is a news story from the New York Times informing me that the head of the Environmental Protection Agency recently said that Trump’s government will “revoke the scientific determination that underpins the government’s legal authority to combat climate change.”

This is what I mean by “nullify the real.” And what the head of the EPA announced is not just a change in policy, but the sound of verification in reverse. It took a long time, a lot of science and many governments, to establish that climate change is really happening. For the Trump government to “revoke” such a finding not only spreads a propaganda claim, it expands what is revocable.

The threat to journalism goes beyond bad information swamping the good. There’s an acceleration factor when all the actors involved in verification (newsrooms, universities, civil servants in government, the legal profession, the intelligence agencies…) are simultaneously under threat.

Jacob: What are legitimate journalists supposed to do about this nullification? Call out dishonest officials immediately and aggressively at the risk of appearing biased? Share officials’ comments with the public and then politely append a correction? Ignore them? They’re making policy, so it doesn’t seem practical to ignore what they say.

Rosen: Study it. Get used to seeing it. Try to develop usable languages for it. Describe and re-describe it when events offer that opportunity. (As against, “We already did that story.”) Develop the “reality rejection check” as successor to the (now overmatched) fact check. Develop denialism as a beat. Figure out how to rank degrees of systematic departure from the real — or instances of “flooding the zone” — then share those rankings with what’s left of the news-reading public.

Journalists can take inspiration from the many public actors who are resisting the destruction of their democracy. And then start featuring them in the news.

Jacob: Can’t the media become much more aggressive than anything you’ve suggested here? Can’t headlines start with the words “Trump lies”? Wouldn’t a confrontational approach be better for the media — and the public — than the current practice of amplifying the lies and correcting them quietly while the independent press dies of 1,000 cuts?

Rosen: Calling things by their right names is a hugely important use of the First Amendment, a case of “use it or lose it.”

The press has to be aggressive, yes, and in multiple ways: digging for information, asking blunt questions (when they are good questions) even if that might endanger a reporter’s future access. Aggressive, too, in warning the Republic that its democracy is under attack, and bringing attention to that warning by use of every media platform available. There’s also a kind of aggression in dispensing with refuge-seeking behavior in journalism — in contrast with truth-seeking.

A list I have circulated many times on Twitter and BlueSky suggests five changes in political journalism that would pay immediate dividends:

Defense of democracy seen as basic to the job.

Symmetrical accounts of asymmetrical realities seen as malpractice.

“Politics as strategic game” frame seen as amateurish — and overmatched.

Bad actors with a history of misinforming the public seen as unsuitable sources and unwelcome guests.

Internalizing of the “liberal bias” critique seen as self-crippling, an historic mistake in need of correction.

So in all of these ways we do need an aggressive press, ready to work in democracy’s defense. If we had more newsrooms devoted to that proposition we would have fewer who seem unable to utter the word “lie.”

I want false claims to be declared false. Clearly and provably. By journalists who are themselves evidence-based. If the best description of what they know is there’s no evidence of that, then say it: “There is no evidence.” If a provably false claim is knowingly used to whip up resentment against a marginal group, there is every reason to call it a lie in tomorrow’s newspaper. What I care most about is that false claims get presented as false. Is that true? Did that really happen?

The word “lie” has no magic powers. Nor is there anything so ghastly about it that editors have to fear its utterance. Use it when it’s most descriptive. That would be my advice.

Before we end this, I want to make one more attempt to distinguish between different levels of falsehood. When recently Donald Trump decided to fire Erika McEntarfer, commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics — because, he said, the monthly employment data were “rigged” — he was acting not only “without evidence,” as the newspapers put it, but in search of his own freedom from fact. This is a further category of falsehood. It not only distributes lies and distortions, it slowly brings to ruin the struggle to inform ourselves. As a worried Reuters put it, “Economists already have growing concerns about US data quality.”

It’s a radical agenda: wrecking at a granular level the means by which we understand our condition and place ourselves in time.

Advertise in this newsletter

Do you or your company want to support COURIER’s mission and showcase your products or services to an aligned audience of 190,000+ subscribers at the same time? Contact advertising@couriernewsroom.com for more information.

Thanks for publishing this Q&A. Jay Rosen's work (especially on "The View from Nowhere") has influenced my own approach to political reporting.

I am not afraid to call out lies when I see them and am confident the politician is lying:

https://laurabelin.substack.com/p/brenna-bird-hid-the-ball-on-major

One thing I struggle with is distinguishing between consciously lying and making a false claim. I get pushback from my own readers sometimes when I debunk a false claim and people say why didn't you just say they lied?

Some of the politicians I cover are profoundly ignorant and/or incurious about the issues. I can't be sure they are "lying" as opposed to lazily repeating a false claim they heard somewhere and may actually believe. (This often happens in the Iowa legislature, when individual lawmakers haven't read the bill and are just parroting the talking points they got from leadership or the floor manager of the bill.)

For those situations, if I don't have evidence they know it's untrue, I usually write that they said something false without calling them a liar. I don't want to pretend to be a mind-reader.

I'd be interested in your take on how journalists should handle this kind of situation—when a politician says something demonstrably false but it may not be clear they know it's false.

I had to give up reading this. I'm not dumb. There's just too much jargon. I don't know the intended audience, but it isn't the average intelligent person. Journalists, to be journalists, need to call out the lies and amplify the truth. They need to ask the hard questions. If they are banned because of it, they weren't getting real answers anyway.